It seems like a fool-proof plan: start up with a close friend. You’ll get along (obviously), and you’ll get to share the exciting, fantastic, scary experience of starting up with someone you care about. It’s not a bad idea, but there are a few caveats that you should be aware of before you proceed1.

When I started my first company with one of my closest friends, I expected things would go very well between us. We understood each other in ways that would take years to build up (and did take 10 years). We knew each other, and we knew we could rely on each other. We were prepared to have many surprises along the way — starting a business is always going to be a scary adventure.

What we weren’t prepared for was that the main problem would come from us and the dynamic between us.

What happened, in brief

I’m not going to go into all the details of what exactly went wrong, for a number of reasons (among them, it would be a one-sided account and inherently unfair on my friend and first cofounder). The long and short of it is, we had different expectations about the business. I left my safe, comfortable corporate job to work on it, so I needed it to succeed, or else I would find myself back in the corporate world. By contrast, my friend had already started several companies and was comfortably well off, so he didn’t have the same expectations and requirements.

It turned out we have a different definition of “the business isn’t working out”. For me, it was working out if it was making enough money to cover my expenses. For my friend, it wasn’t working out unless it was making enough money to also add to his existing wealth and thus justify the time and effort which he poured into it. Both those views were correct, but because we knew that we understood each other, we didn’t realise that our views were different until that difference had grown into a huge misunderstanding.

This core divergence of views could have been resolved easily if we’d known about it and discussed it ahead of time, but we didn’t know about it, so it festered and turned into dozens of other misunderstandings, so that by the time it finally became clear what our main divergence was, much of the damage was already done and it was entangled in a huge mass of emotional misunderstandings2.

This almost cost us our friendship. We got through this thanks to the help and mediation of another very good friend, who helped us to communicate to each other how we felt, so that we could move forward together rather than against each other.

I’m glad to say the mediation worked, and we’re still friends (perhaps even stronger than before). Nevertheless, I learned some important lessons from this.

1. Make your agreements explicit

The first lesson is to keep agreements explicit. It’s not enough to think that your friend understands what you think: make sure he does by discussing it openly with him. As my mediating friend phrased it, “unspoken promises” have a tendency to turn into broken promises (which are always hard to swallow). Avoid unspoken promises.

Here’s an example of a really bad thing to keep implicit: “We’ll only call it quits if the business is bankrupt and can’t raise any more money.” The promise here is that we’ll keep going until the very end. This may seem obvious to one party in the business, but it may not be so to the other. One partner could, for instance, feel that the time to call it quits is when the business has 3 months of cash flow left. Another may feel that it’s worth going deep into credit card debt territory before giving up.

Don’t make this mistake: keep those agreements explicit.

2. Detail your agreements

Once you make some agreements explicit, it should become clear that you need further discussion to figure out exactly what your explicit agreement is. Don’t be afraid to do this. It’s not “too early to discuss this”.

Here’s an explicit agreement that’s not detailed enough: “We want the business to make a lot of money”. Really? How much are you happy with? 10’000 pounds a month? A million? What is the definition of success? It’s almost certain that you and your business partner have different views as to what “a lot of money” is. Being on the same page about what you expect out of your business will ensure that you don’t pull in different directions when things are going well. Think of how mortifying it would be to find out that your partner wants to pull the plug when you think that the business is successful.

3. Don’t be afraid of discussing the bad stuff

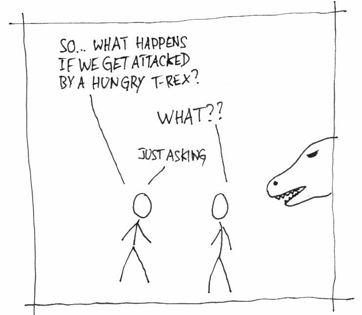

There are a number of subjects which seem almost embarrassing to discuss when things are going well. For example, “What if one of us decides to pull out?” Your first reaction to this topic might be “What? We’re barely getting started, and already we’re talking about what happens if one of us pulls out?”

The reality is that people’s life circumstances change through time. They get married, or decide to leave the country, or get engrossed in a different pursuit, etc. Many things can get in between a founder and his start-up. Similarly, many things can go very wrong with a start-up. When those things do go wrong, or when one of the founders decides to pull out, is not the time to discuss these things. You need to discuss them with a clear head when no one is thinking of pulling out and the business looks healthy and hopeful.

When you discuss your start-up’s future, do not be afraid to talk about the disaster scenarios. Also, when you negotiate what will happen if a partner quits, don’t be so sure that it won’t be you.

4. Write things down

There are two reasons to write things down: first, people’s memories of conversations are faulty. Writing things down also ensures that there is no disagreement, later, about what was decided. You don’t need a long document for this — even just one or two pages describing your agreement is enough to avoid later misunderstandings.

The second reason is that people may think they have reached an agreement when in reality they never agreed about the details. Once you put something in writing, you give it a certain air of finality that teases out those last remaining disagreement. Basically, putting an agreement in writing is like putting a new piece of functionality in code. Until it exists in that form, it’s just vapour.

Halfway through my misunderstanding with my friend, we thought we’d figured out a way forward. I wasn’t sure that we were both thinking the same thing, so I made the effort to put it in writing, in the form of a business plan. When my friend read it, and understood more clearly what I meant, he recanted, and the agreement fell through. It’s a good thing that it fell through, because it would likely have resulted in even more problems later on if we’d gone through with it based on our flawed understanding of each other.

5. Don’t make it work at all costs

Yes, I know this is your friend that you’re starting up with, and this is your great opportunity to start your own business. However, if, in those discussions, you find that there’s an intractable disagreement, don’t fall into the trap of thinking that the most important thing is to smooth things over and start the business.

Starting up with someone is almost like marrying them (temporarily), in a way. You’ll be talking to them almost everyday, and possibly even more than with your significant other. You’ll be working on a “baby” (your business) for many months. It’s a big commitment, basically, and much like any other kind of significant commitment, you shouldn’t go into it if you think there are major problems, because those problems will only get worse.

6. Don’t assume things will get better with time

It’s easy to rationalise away big problems by assuming that things will get better with time. In some cases, they will, but in a majority of cases, they won’t. What this means, for example, is that you shouldn’t assume that your inexplicably small share of the business will magically grow to 50% later on. This is even less likely to happen if the business is working well (if the business isn’t working out, chances are it doesn’t matter anyway).

Sample questions

This article wouldn’t be complete without a list of questions that you might go through and discuss with your cofounder. Use them as a guideline or as a checklist, as you please.

- What do we both mean by “the business is successful”?

- What do we both mean by “the business is not successful”?

- What happens if one of us needs to voluntarily pull out, for any reason?

- What happens if one of us cannot work on the business anymore, for involuntary reasons?

- What are the conditions under which we’d call the business a failure and pull the plug?

- What is plan B for each of us if we do pull the plug? Are we both prepared for that plan B?

- What do we expect of each other, both in terms of responsibilities and in terms of attitude and effort?

- What is and is not an expense? What is the maximum amount someone can spend on an expense without checking with the other? (from Sebastian Marshall)

- When and how will profits be distributed? How much will be reinvested? What will the reserves be? (from Sebastian Marshall)

- What happens if one partner needs cash and the other wants to reinvest it into growth/expansion? (from Sebastian Marshall)

- How will you handle it when (not if) the hours each partner is working are unbalanced? (from Sebastian Marshall)

This is not a final list by any means, but it should at least provide some starting points to make the implicit explicit. If you have other suggestions, please do add them in the comments below.

Conclusion

I don’t regret starting that business with my friend, but I do regret not clarifying those kinds of questions upfront. It would have saved me a lot of worry. If your business is struggling, you don’t need the additional pain of seeing your friendship unraveling under the stress of accumulated misunderstandings.

So, do yourself a favour, and set out to:

- Make your agreements explicit so that you don’t break implicit promises

- Detail your agreements so that your promises are clear

- Don’t be afraid of discussing negative scenarios, so that you don’t add the stress of misunderstanding to already bad situations

- Write things down so you’ll remember

- Don’t make things work at all costs, so that you don’t spend the next years living with a deal that’s not acceptable to you

- Don’t assume things will get better with time, so you’re not surprised when they don’t

I hope this helps others. Your comments below are much welcome.

1 It’s worth adding that this advice can be useful for any kind of adventure, not just business. However, given the propensity of businesses to crank up the pressure to diamond-producing levels, and what can often be at stake, it’s particularly important in this context.

2 Although this sounds like a barely mitigated disaster, I must add that, on the whole, the business was a success (it made money, I learned a lot from it both about myself and about start-ups, and it provided a jumping board from which to start my next business). It wasn’t as much of a success as it might have been, and there were some times when it looked like it might turn into a small disaster, but on the whole it turned out reasonably well.