What’s the worst thing a founder can do to their NFT project?

The quick answer, “to rug it”, is correct but also ambiguous. We don’t have an agreed definition of “rugging”, so ppl get lost in arguments about whether this or that was a rug, and lose sight of what matters.

Of course there are obvious examples like Frosties (currently arrested by the DoJ), where a founder literally takes the mint money, deletes the project and walks off. We can all agree that that’s a “rug”.

https://nftevening.com/frosties-nft-20-year-old-founders-arrested-on-suspicion-of-fraud/

But most founders, even scammers, aren’t quite that dumb, and so they’re a bit more subtle in how they rug. Hence the concept of the “slow rug” has emerged, as a way for rugging founders to claim innocence.

In the wake of the Frosties’ arrest, many previously dead projects re-emerged briefly and started posting updates, so they didn’t look so obviously like rugs. A good ass-covering technique, I suppose, though we’ll see what the DoJ thinks about it eventually.

But one concept that’s emerged recently is that “it’s ok to have failed projects”. It’s a very tangible and valuable truth from the startup world that is unfortunately being twisted around and made into another evolution of the “slow rug” con.

First of all, let’s acknowledge: yes, it is ok to have failed projects.

If NFT projects are like startups, which I believe they are, then many will fail. One of the great innovations of the American funding machine has been to not regard failure as a badge of shame.

In most of the rest of the world, failure was unconscionable. The problem with that attitude is twofold:

- it discourages ppl from taking the risk of starting something

- it discounts the huge learnings that come from starting and failing, which can be carried to the next venture

So I 100% agree that it’s a net gain for society and the nft space to embrace the idea that founders can fail, and that they might still be trusted and funded in their next project.

Failure is an almost inevitable part of the journey.

But…

There are failures, and then there are half-assed attempts.

And there are ways to conclude a project cleanly once it fails, and there are ways to behave like an asshole.

Both of those are important factors that need to be considered.

The first one is the most subjective, and hardest to evaluate. Did the founder(s) really give it their all? Often you have to take their word for it. And it’s difficult to judge, because being an armchair founder who says “well I would have done it differently” is a load of crap.

In the life of a startup, or an NFT project, every day there are a whole bunch of small and big decisions you have to make, often quickly, under pressure, without the benefit of hindsight, and with extremely limited information.

It’s easy for someone to come later and point out how you could have done better. It’s much harder to actually do better in the circumstances.

So I think there it is worth, typically, giving the benefit of the doubt to founders.

Only they know if they truly tried their best.

The second point, though, is much more clear cut.

How did the founder(s) end the venture?

Last impressions matter a lot. How someone leaves, when they feel like there is nothing left to gain, speaks volumes about their character.

I employed many dozens of people over the years, and I always left a lot of leeway (with some guard rails to prevent legal troubles) around how people structured their departures. Part of it was because I thought that’s the right thing to do. Part of it was because I was curious.

People’s characters reveal themselves much more clearly in those last few weeks. Some do their best work then, finish whatever can be finished, and leave on a high, perhaps with lifelong friendships with this group of ppl they used to work with.

Others… do less well. And in their departure, they reveal something about themselves that you could probably not have gotten out of them in many other circumstances.

Let’s go back to founders.

Founders typically have responsibilities to four main stakeholders when winding down a startup:

- their staff

- their customers

- their investors

- the government

All should be tied up cleanly. But only one will land you in jail if you botch it up.

When the story came out about Ryan Carson mistreating his staff while winding down Treehouse, that was a strong negative against his character. Did he “rug” Treehouse? In a sense, yes. If the article is to be believed, he rugged his staff, who had worked hard for him.

When companies end, it matters how founders treat people.

Here we are mostly concerned with investors.

Investing in a company that subsequently fails is not a new thing. There are ways to do it and ways not to do it.

Here’s what is typically expected of a startup founder whose company fails – this, despite the fact that having to declare failure is a deeply traumatic event for most founders, so they definitely have a lot of excuses for being less than perfect in those times:

– First of all, founders should be very clear in communicating what is happening. Investors should find out from the founder that the company is likely heading for failure, not from some other source, and not the day after the failure becomes official. They should see it coming.

– Secondly, founders should offer investors chances to ask questions and, in some cases, hold space for them to vent, etc. Investors are humans too, much like the founders, and some of them will be quite shocked. Not everyone is a calm professional investor.

In the startup world, that’s especially true if the founder raised funding from “FFF” sources (Friends, Family and Fools), who are not used to losing £10k+ and so will need some support to come to terms with it, which is one reason why many experienced founders avoid FFF funding.

In the NFT Startup world, that’s even more true, because most investors are not professionals, they are just starry-eyed NFT believers who had faith in the founder’s vision and bought in – some with their life savings or debts they took on.

– Third, startup founders are expected to do their best to make the investors whole.

Of course that’s not possible most of the time (or else the startup wouldn’t be failing). This usually happens 3+ years after fundraising. The money has all been spent.

In those cases it can often be expected that the founders will nevertheless liquidate the company, sell off its assets as best they can (perhaps including any IP they created), and distribute the proceeds to investors.

What should never happen is for a founder to raise millions, pay themselves millions upfront, give the startup a go, change their mind, and walk off with the millions.

That’s just unconscionable.

In the regular startup world, such a founder would never be trusted again.

Hell, in the startup world, because of investor protections, they would likely be found to have not behaved in the interest of shareholders and breached their director duties, and could be sued for it.

What happens so regularly in the NFT world is incredible in comparison.

NFTs are not shares, so NFT investors don’t have the same rights as shareholders.

A lot relies on trust between the NFT holders, and the ppl running the project.

So if a founder breaches that trust, there is no legal recourse.

The only thing we can do is not trust them again.

Adapting these three criteria to the NFT world, I think these are the minimum expectations we should have on a founder who chooses to end a project or leave it:

- Communicate clearly and early

- Hold space for questions

- Do what they can to minimise financial losses

A founder who doesn’t do their best at these three points didn’t just “fail at a project”. They failed at being at trustworthy human being. And in a space where so much is based on trust, they should not be trusted again by anyone sensible.

Which brings me to the debate of the day… Whether Zagabond rugged or didn’t rug his past projects, and what should be done about it.

Disclaimer: I have not done extensive research in this. Maybe I’ll get some facts wrong.

But from what I have read, it appears that Zagabond simply left the projects he started in the lurch, without communicating anything, let alone holding space for questions or trying to minimise financial damage.

Yes, 300%, Zagabond seems to have rugged those projects.

It’s not even about whether he “delivered on the roadmap” or not. That’s irrelevant. Leaving a project that people are financially invested in without a word is exceedingly poor behaviour. Whether he can justify it by waving the word “roadmap” about doesn’t matter.

It’s just not the decent thing to do if you want people to trust you.

And if you want to keep working for a prestigious project, you should want people to trust you.

That’s not the worst part in the Zagabond saga though. The worst is the Mirror article.

As far as I can tell, Zagabond doesn’t even feel the slightest bit of remorse about abandoning those projects in this way.

So not only (if it is correct that he ditched them abruptly) did he rug his past projects: he doesn’t even recognise that he did anything wrong.

Can you choose to trust someone who does something unethical and then shows no remorse about it?

If you do, I have a bridge to sell you.

(I don’t. I’m not into that kind of business. But many people do, and you and your money will soon be parted.)

It’s hard to communicate that things are going badly, admit failure, move on, etc, in a public space like NFTs.

And if you’re going to ask for thousands of ppl to trust you with vast sums of money, pull up your sleeves and get working hard to earn that trust!

As for what should be done at this point. Well, that’s for the ppl running Azuki to decide (see note about armchair founders). That said, I think Kevin Rose offered a good example of what to do recently, and they could do worse than follow that example.

Good luck to all involved either way.

And remember: how you leave matters just as much as how you enter.

gm & gl

Original Thread:

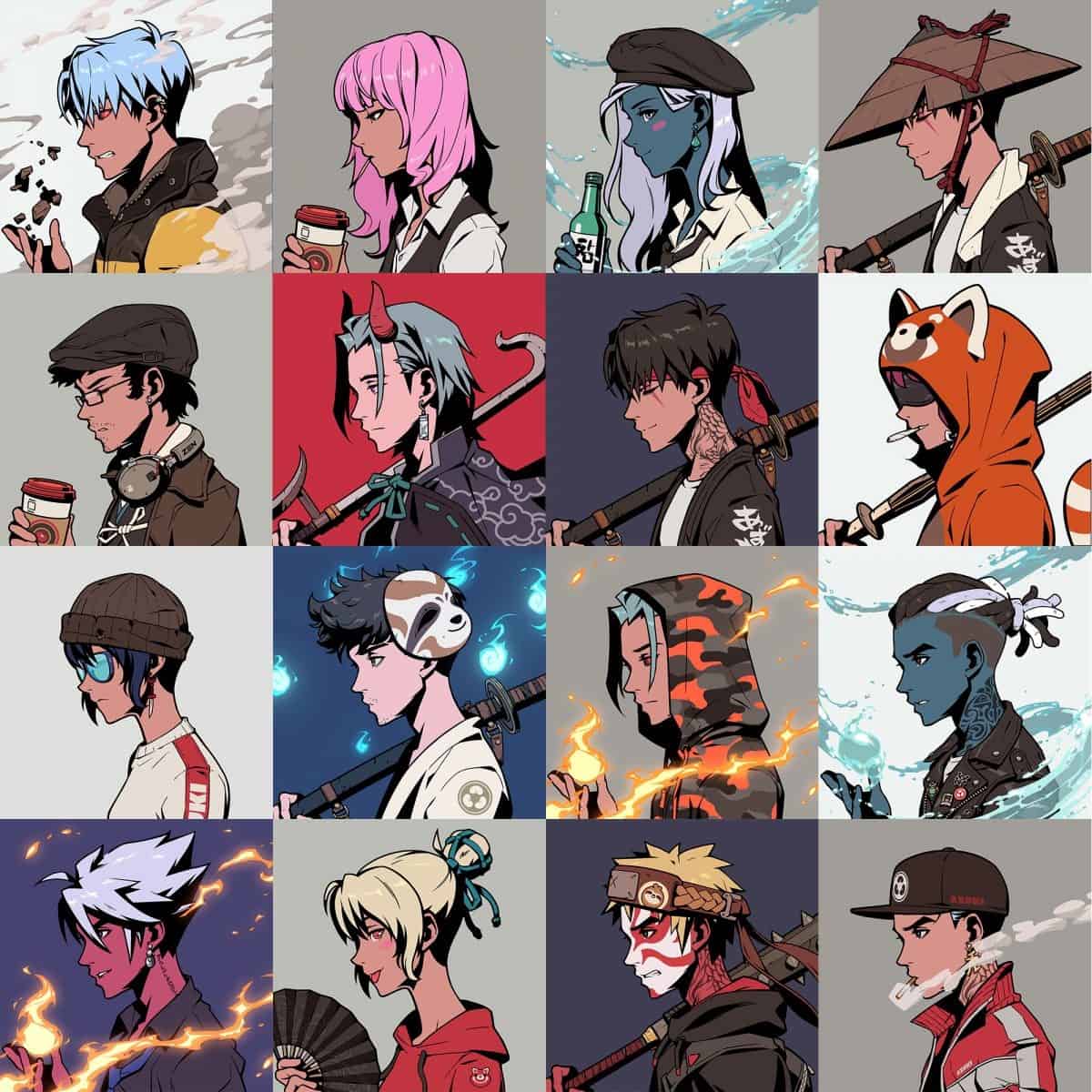

What's the worst thing a founder can do to their NFT project?

The quick answer, "to rug it", is correct but also ambiguous. We don't have an agreed definition of "rugging", so ppl get lost in arguments about whether this or that was a rug, and lose sight of what matters. pic.twitter.com/1pmpXfEsGb

— Daniel Tenner (@swombat) May 10, 2022