Image courtesy of flushirts

Everyone wants their application to “spread virally”. And why shouldn’t they? Viral growth resolves at least part of the expensive and complicated headache of actually marketing your application, by getting the application to grow all by itself. So, then, the question that forms on the lips of any entrepreneur is:

“How can I make my application viral?”

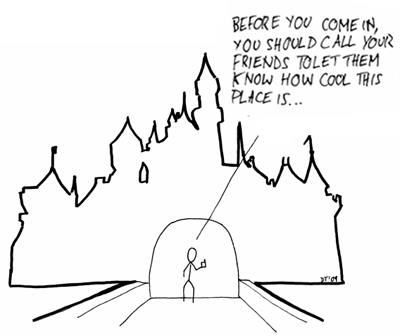

There’s a misconception built into that question: the idea that virality is something that you can just slap onto any product, like a magical pixie dust that will suddenly grant your application the gift of users.

“Making an application viral” is as silly a proposition as “making a car fly”. Sure, it’s technically possible, but that requires a lot of fundamental changes, and what you end up with is not a car anymore (or perhaps it was never a car to begin with).

However, what you can do is set out to build a plane in the first place. There are some building blocks that you can use or omit in your application design that will enable or hinder your application’s virality. This article explores some of those building blocks, with the aim of at least helping you make your next application spread virally1.

Viral basics: the viral loop

There are plenty of articles talking about the viral loop, so I’ll cover it quickly in this article. The main focus is not the theory of viral growth, but some practical things you should keep in mind while designing your product, so that this viral loop does work for you2.

The cornerstone of all discussion of the viral loop considers the cycle from acquiring a new user to having them invite others. In equation form:

viral coefficient = (average number of users invited by each active user who invites someone) x (proportion of invited users that actually join or become active) x (proportion of active users that invite others)

or, using variable names that we’ll refer to later:

VC = N x P1 x P2

If your viral coefficient is greater than 1, then over time your growth will increase exponentially, and you will saturate your market (or whatever parts of it you have access to, if your market is highly fragmented). If it’s smaller than 1, your growth spurts will always end and you will have to keep pumping marketing energy into your application to grow it (which, as this article points out, may not necessarily be a bad thing for some, since it puts you in control of your growth). If it’s 0, you won’t get any viral growth at all.

This idea of a viral coefficient is very powerful. If you can measure it, and break it down into the correct factors for your application, it can tell you what specifically you need to improve in order to increase your viral spread. So it’s definitely worth measuring this coefficient, even if your application is already spreading virally.

Practical virality

So, with that in mind, how do you actually get your users to invite more users? The brutal, dirty answer would be to slap on a form that asks for their email password and hoovers up their contacts. Many early Facebook applications used similar tricks (in fact, Facebook themselves did so), and the result of that was incredible growth, but also a lot of spam. Facebook soon shut down these holes as far as applications were concerned, and they were right (if a tad hypocritical) in doing so. In my opinion, if you rely on abusing people’s contact lists for your viral growth, you’re only a few rungs above ordinary spammers. Many reputable companies still do it today, but I don’t think this is something they should be proud of.

Before we go into the principles of how to build a viral application, it’s worth emphasising this again: viral growth does not and should not require dirty tricks. I do not condone any form of spam or other abuse of your users’ precious trust, if only for the reason that once users stop trusting you, it is very difficult to regain that trust – as far as business applications are concerned, this sort of behaviour can kill your reputation dead. None of the principles below require any form of underhanded behaviour to be effective.

The golden rule of the ethics of viral spread is: try to only do things on a user’s behalf when they’ve explicitly done something to request that thing, and they know that what they’ve done will result in a communication being sent on their behalf. If you can’t link an invitation directly to the inviter’s action, then you probably shouldn’t send that invitation.

Virality principle 1: Inviting as a core process

Once upon a time in 2007, I was tearing my hair out as to why my Facebook application (now defunct) just wasn’t spreading, and I cornered R. Tyler Ballance (who created the highly successful “Top Friends” facebook application) into a private chat on IRC, to exhort him to give me the secret of building a viral app. Although he didn’t quite give it away, he did provide a handful of hints that pointed to one of the key answers.

The first step in increasing your Viral Coefficient is to increase N, the average number of users that each of your active users invite. The most effective way to do this is to ensure that inviting other users is a core process in your application, rather than something that people are asked to do as an afterthought.

In other words, the most viral applications are those that involve inviting others to the application as part of the daily usage.

Update: Some people have pointed out that this section is not entirely clear. What I mean is this: certain kinds of applications (e.g. collaboration tools) lend themselves to the concept of inviting others, as part of the core usage of the application. If you can architect your product so that it is one of these applications, that will greatly enhance your viral spread. This cannot be latched onto any application. It needs to be as integral to your application as “getting people wet” is integral to the use of a water pistol.

Examples

Top Friends did that extremely well. The core usage of Top Friends is to select your top friends and rank them. As part of this process, you are naturally asked to tell the friends about this ranking business, and thus they are invited to use the app themselves.

Woobius (my business) has also integrated the invitation process successfully: part of the core usage of the application is to invite collaborators to a project.

Hotmail, the grandaddy of them all, was one of the first mega-viral applications because each email included a small advert at the bottom, that invited the recipient to join hotmail.

Paypal also hit the nail on the head by allowing users to send money to people who were not registered yet (they later doubled up on that by giving a referral bonus if you got the recipient to join). Paypal is about sending money to people, and inviting them as part of the money-sending process was a stroke of genius.

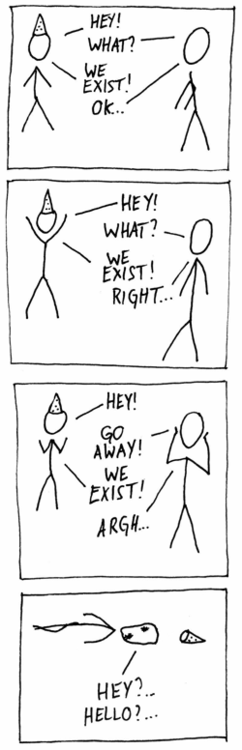

Virality principle 2: Keep pulling people back in

It’s not enough to invite people, of course, you also have to get them to actually join up (coefficient P1 in the earlier equation). There are several ways to do that, but one of the essential, practical things that your application should do to get them to join is be persistent.

What this means is that you should not just send them one invitation and then wait for them to join. And once they’ve joined, you should not just wait for them to start using your system and inviting more users. You should keep sending useful communications and/or showing signs that will encourage people to use the system. Of course, this also needs to be a core process of using the application. You can’t send people reminders all the time without a good reason – that would be spam.

When you pull people back in, you should not only remind invited people that they can join, but also remind your active users that they can invite more people, and that there are benefits to doing so.

Examples

Hotmail, again, got that exactly right. Since every email included an invitation to join Hotmail, and promoted hotmail by coming from an @hotmail.com address, every email implemented the “keep pulling” effect.

Mob Wars, a Facebook game, applies this concept by constantly reminding its users that new features will be unlocked if they invite more of their friends.

Facebook itself does this extremely well. I can’t count how many times I’ve drifted away from Facebook, only to be dragged back when someone posted to my wall or sent me a message. Because of this, I (and many others) still pay attention to Facebook every week or two, even though I don’t actively use it.

Virality principle 3: Be useful even with no other users

This is also known as the “chicken and egg” problem. It’s what killed my Facebook application, back in the days, because that application was useless unless some of your friends had also signed up. It’s possible to succeed despite this problem, of course, but it’s much, much easier to spread without it.

This doesn’t mean that your application shouldn’t benefit from network effects (i.e., the effect of becoming more and more useful the more users join). It does mean that there should be some modicum of useful functionality that works and is immediately useful even when none of the user’s contacts have signed up. Even in applications like Twitter or LinkedIn, which are really all about the network effects, the fact that there is something meaningful for the user to do right away, even when they know nobody, is a huge plus.

Most users will not invite other people when until they’re familiar with an application. If you don’t provide them with something to do before they’re ready to invite others, you will probably lose them long before they reach that stage.

Examples

Twitter, funnily enough, got this somewhat right. By presenting itself as a micro-blogging platform and providing a “What are you doing?” prompt, it provides an immediate piece of functionality that users can start using even when they don’t know anyone else on the network (even though it is a little demoralising for some people to write mini-blog posts that no one will read).

Woobius achieves this because a new user can use it to send files to other people even if those other people have not joined. Similarly, the revision tracking functionality works well even if only one person uses it.

LinkedIn, despite being mostly used for its connections, provides an immediately compelling functionality for new users, by allowing them to recreate their CV online (which is a big deal for many people who are not so tech-savvy).

Virality principle 4: Remove artificial invitation limits

If you’ve ever built an application with viral spread, you’ll have noticed something that’s not very obvious when you look at the Viral Coefficient equation. At first glance, it would seem that growth should be smoothly distributed… each user invites an average of 10 other users, of which, in turn, 20% end up becoming active users and inviting another 10 users. It all seems quite easy and… smooth.

Except it isn’t. In practice, most people invite no one. Just like with other human relationship networks, invitation patterns have a few strong focus points, highly connected nodes that result in dozens or hundreds of invitations, and a lot more weak end-nodes who rarely invite anyone.

We’ve noticed that on Woobius too: most people invite no one, but a handful will invite 40 people at a time.

What this means in practice is that the last thing you want to do is to limit how many new users each existing user can invite. This is an important lesson, because when designing Software-as-a-Service applications, it seems very reasonable to charge based on how many users use the system (after all, many leaders in the field do so). Even easier, one might be inclined to make the “free” version support only one user.

One way to resolve this problem is to ask yourself what would happen if someone who just joined my application thought it’s great and wanted to invite 20 of their friends/colleagues? If you can’t provide an easy way for that person to market your application for you, you’ll lose out on your best inviters.

Examples

MinuteBase, a recently released minute-taking application, started off with a limit on the number of users, but decided to remove that limit. After only a couple of months live, this has already resulted in faster viral spread than the initial concept of limiting free accounts to a single user.

As a counter-example, most products built by 37-Signals do the exact opposite. They limit the number of users (so you’re unlikely to invite someone unless you really must), and even force their own users to fragment into multiple subdomain. This obviously works for them, so I’m not criticising that as a way to do business. However, from the point of view of viral growth, it is very ineffective, and it is likely that 37-signals gets most of its users not through viral spread but through their more traditional marketing activities (their blog, their conferences, and, of course, their link to Ruby on Rails).

Summary and conclusion

There are many other things you can do to tweak the viral coefficient and improve the spread of your application, but carefully considering these points will get you further than most:

- Invitation should be a core process, that is essential to using the application – this will maximise the chances that your users do invite new users.

- Keep pulling people back in, rather than letting them forget you after the initial invitation, and make this “reminder” process also be central to the use of the application.

- Be useful even to the lone user, because that lone user is the source of all your other users.

- Remove artificial invitation limits, to recognise the reality that most invitations come from a few very active users, and help those users spread the word.

These concepts, as I mentioned earlier, cannot be applied to all applications. Some applications are simply not going to spread virally. But if it is possible to tweak the application design, early on, to accommodate these principles, the result should be increased, viral, self-sustaining growth.

Many thanks to Bob Leung, Tom Hastjarjanto and Cliff Rowley for reviewing drafts of this article.

1 Some existing applications may even lend themselves to retrofitting wings and turbines. Your mileage may vary.

2 It’s worth noting that not all apps have to be viral. There are many ways to achieve high user growth, and virality is only one of them (though it is certainly one of the cheaper and more scientific ones).